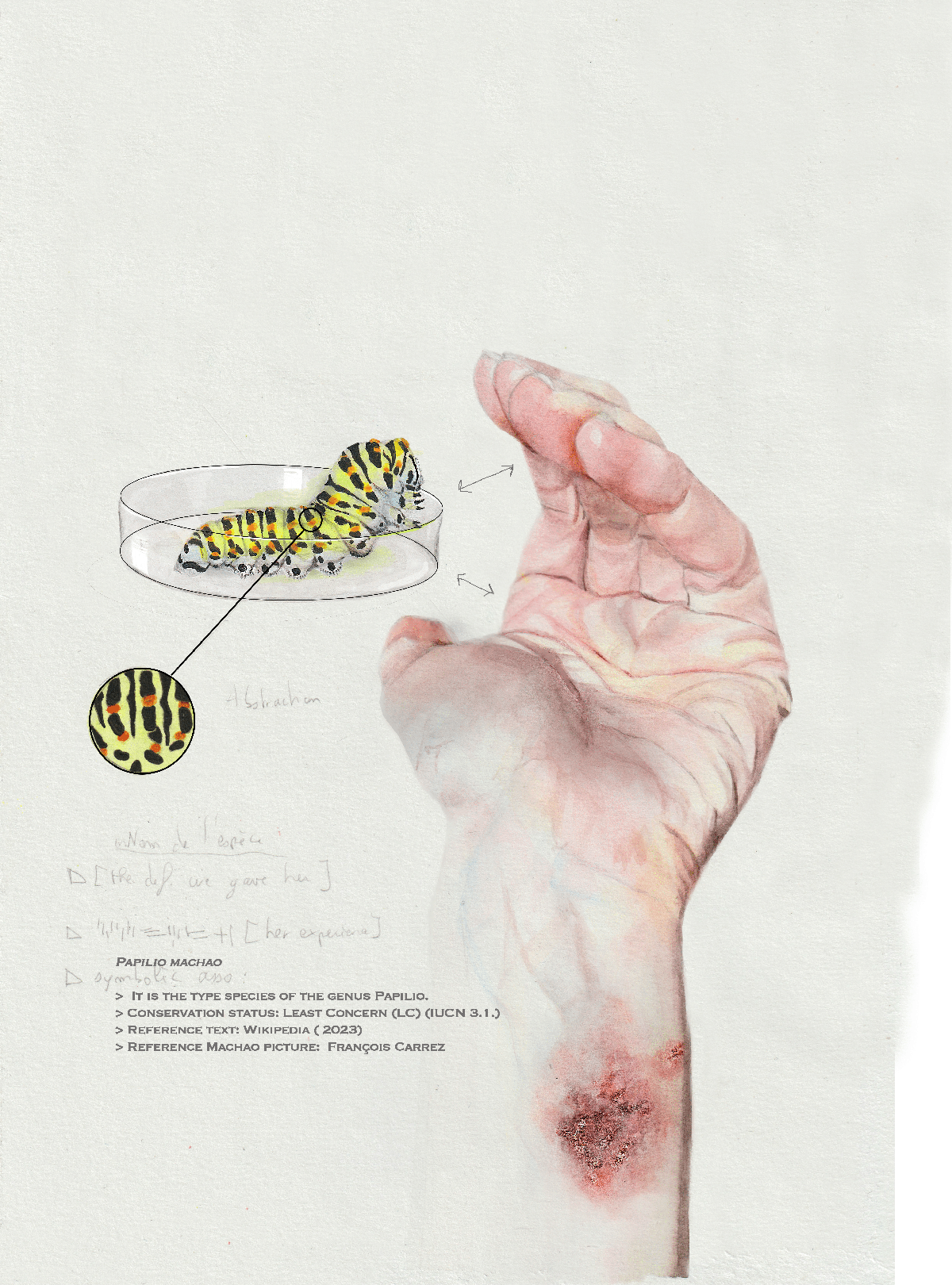

Papilio Machao

As a child, I often tried to farm small breedings of tiny creatures – snails, baby fishes, stick insects, ladybugs, praying mantis. Once, I put the two latter in an empty watering can, to observe the predator-prey dynamic at work on a small scale. Soon, only one insect was left in the improvised arena, surrounded by tiny red shell pieces.

The spectacle was complete, and I was both thrilled and repelled.

Another time I rescued a big buzzing bluebottle from the threat of my mother’s fly-swat, and comforted it in my small hands as if it needed to be.

My brain decided these two memories were worth saving, among other snapshots of insect life from my childhood.

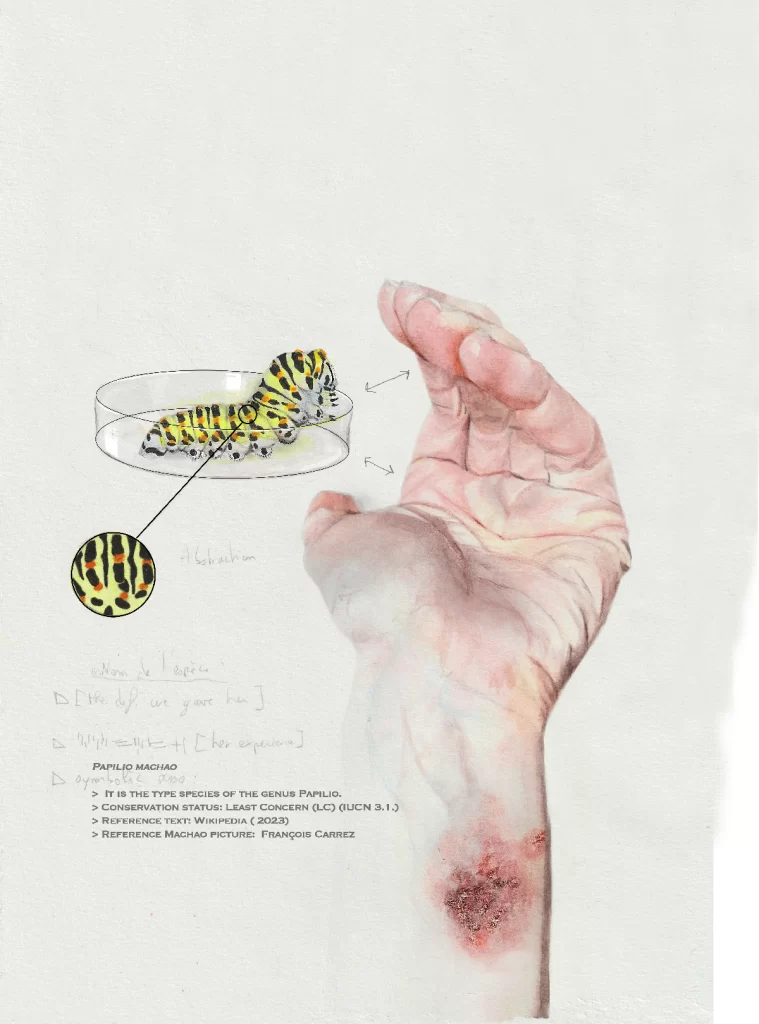

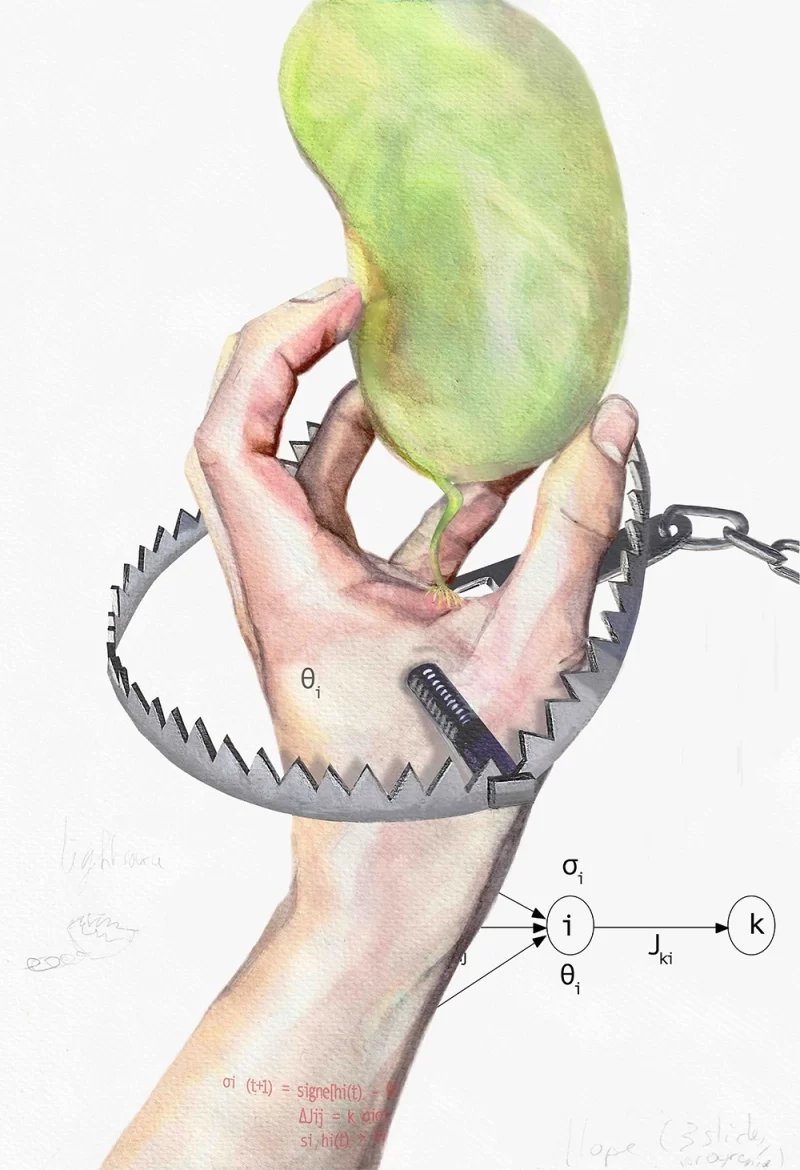

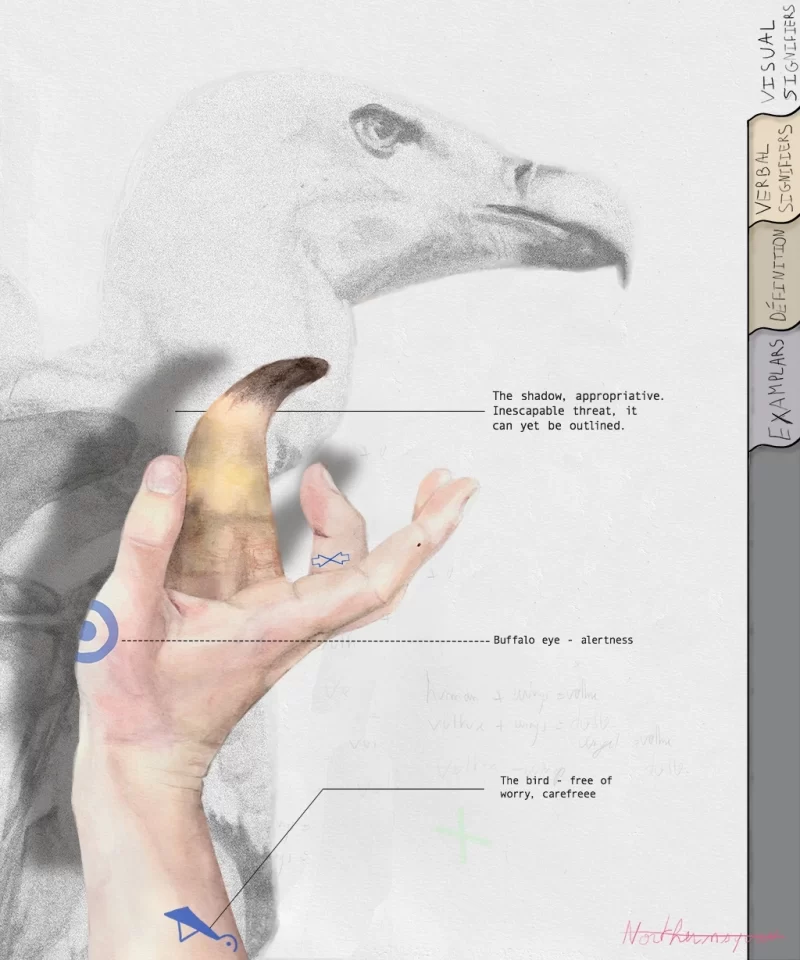

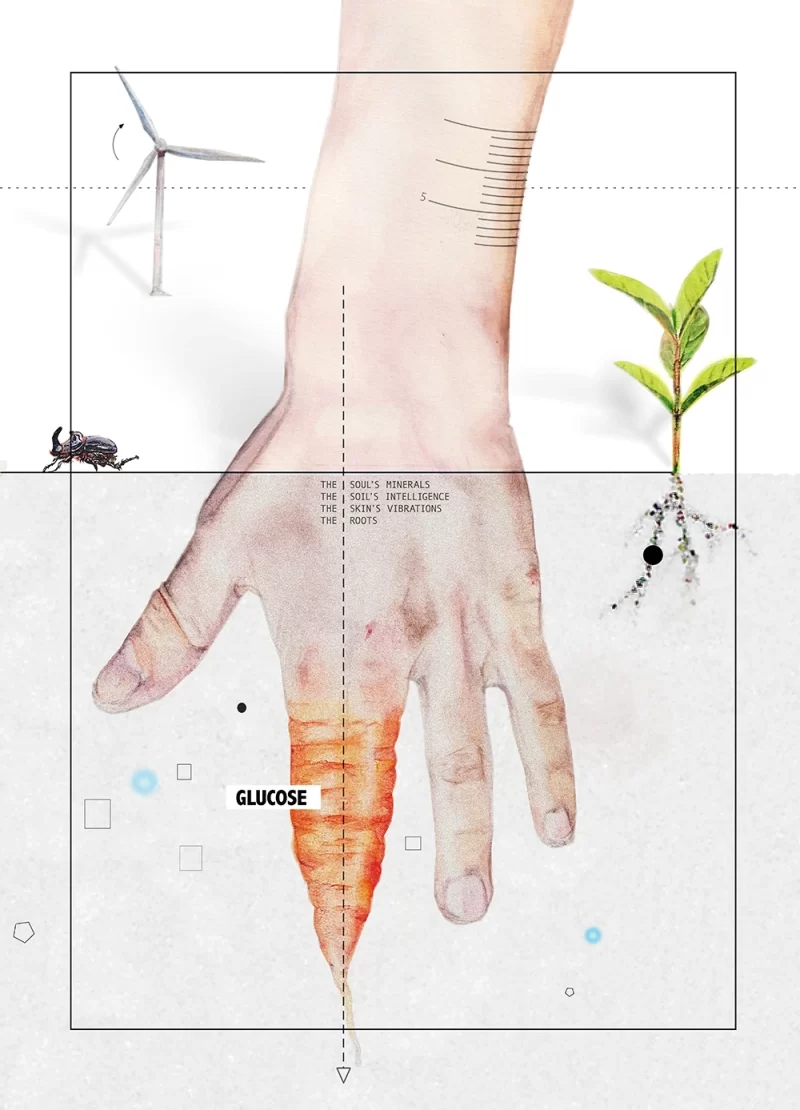

Our relationship with insects is an ambiguous one. So tiny they are that they seem to have been made for our fingers to play with. (That may be why they were equipped with scary gruesome features, to keep human fingers at bay???). We use them for pigments, silk, crops and organic gardening, honey, composting, cosmetics, wound cleaning, proteins, inspiration, decoration, and more. And yet curiosity and fascination are quickly circumvented by dread when they appear near or within something we deem our own: the human creature creeps within itself, fight or fly, instinctively responding to remains of Darwinian competition.

My house.

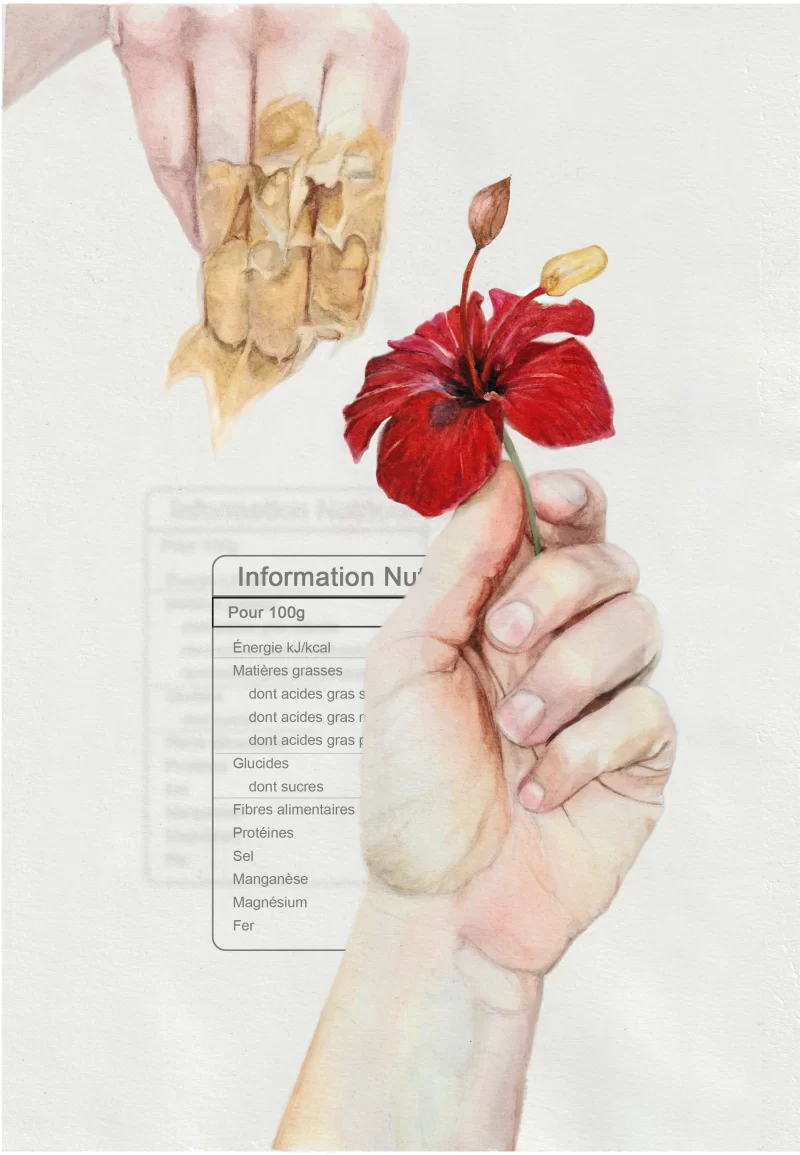

My food.

My body.

Yet I believe that this is not a matter of ownership. It is pure dread. It reveals a glimpse of a weakness in the denial of death, our shield, as one creeps within when the other creeps out from its mysterious corners of the earth, freaked out.

Follow-ups:

What would be the place of insects in a truly ecological society?

Would they be some of our staple foods? How representations would need to change for it to become the norm?

Would they be neighbours/ housemates/ co-inhabitants we just accept to live with because pesticides would have been banned?